It’s easy to see the Coralwood is in the pea family. Photo by Green Deane

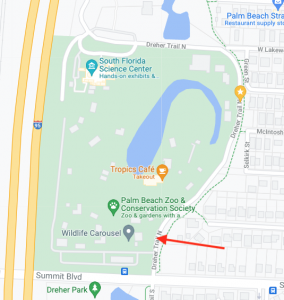

The arrow marks the spot of the Coralwood tree outside the WPB zoo.

Chance happens in foraging. More than once I have passed a tree several if not dozens of times but never noticed because it was not in bloom or seeding. It happened again this weekend in Dreher Park in West Palm Beach. (That’s how I discovered the barely edible Spanish Cherry Tree there a few years ago. It was fruiting when I was there.) This time my unknown tree was extremely heavy with pods and seeds and hard to miss. Unfortunately I failed to bring some seeds home with me. There was a suggestion it was a Coralwood Tree, Adenathera pavonina. Research suggests that was a correct identification. Better, it has some edible parts but not without controversy.

The Coralwood is an Old World tropical tree. In the New World it has been introduce from Venezuela to southern Florida. The species is a nitrogen fixer, provides animal forage, is a garden ornamental, and has a huge array medicinal uses. Where’s the conflict? Well… there really isn’t one. It is more like internet fog and splitting hairs.

Coralwood seeds are usually weigh a quarter of a gram each. Photo by Green Deane

Cornucopia II, a standard reference, says on page 152 “Seeds are eaten raw, or roasted and shelled and eaten with rice, tasting like soy beans. The husked kernels contain 25% of their weight of oil with a protein content of 39%. Young leaves are cooked and used as a vegetable.” That is from the 1998 edition of Cornucopia II. The Internet, however, cutting and pasting from Wikipedia, likes to reference an 1889 Australian book that they say says the uncooked seeds are toxic. I happen to have a copy of that book: “The Useful Native Plants of Australia” and it does not say the seeds are toxic per se but rather the family. This is exactly what the author, J.H. Maiden, wrote on page 5:

“In India these seeds are occasionally used as an article of food. They are the size of a kidney bean. They would doubtless require boiling, or some similar preparation, for it should be borne in mind that the Leguminosae must be regarded as a poisonous Natural Order in spite of the fact that it yields some of the most valuable foods used by man and beast.”

In my foraging classes I tell students the pea/legume family is not a friendly one. What Maiden wrote is far from saying Coralwood has toxic seeds. He wrote a warning in general about the legume family (which holds true for uncooked kidney beans for example.) We are not, however, clearly off the poison hook. There has been substancial research on the species as food for humans and animals. In all the studies I read the seeds were cooked and the shell discarded The cooked seeds were made into everything from a nut milk to ground chicken feed. One research paper suggested the “toxin” might be a trypsin inhibitor. That reduces the breakdown of digested protein thus preventing the body’s utilization of the protein. Like a protease inhibitor — also in legumes such as groundnut, Apios americana — that can lead to severe digestive upset. Cooking would reduce the trypsin inhibitor as cooking reduces protease inhibitors. You can read more about the Coralwood here.

Kudzu blossoms are used to make a grape-like jelly. Photo by Green Deane

There are several ways to find plants while foraging. Once you study them they tend to stand out among their non-edible peers. That said I always find Kudzu with my nose: When in blossom the air smells like a room full of third graders all chewing cheap grape bubble gum. It’s an unmistakable aroma and far more intense than grapes themselves. We detected some this past weekend during a foraging class in Cassadaga. What is odd about the plant in that park is the state says it is not there (and the wild pineapples are not there either.) Out of sight, out of mind. All parts of the kudzu is edible except the seeds. The problem is the leaves have a texture issue even when cooked. It is better if they are processed by a goat into milk. Goats relish kudzu and are a solution to the invasive species. You can read more about Kuzu here.

Classes are held rain or shine or cold. (Hurricanes are an exception.) Photo by Kelly Fagan.

Foraging classes: Hurricane season is not over. In fact this is the peak season so we may end up dodging tropical tempests. Also note my foraging classes in South Carolina are just a month away. Mark your calendar. That weekend I will be holding two classes a day, 9 and 1 which should accommodate everyone’s schedule and temperature preferences. I know my cousin Lenard and his wife Donna are looking forward to hosting this event again. You can email me to let me know you are attending — GreenDeane@gmail.com — or email them at putneyfarm@aol.com. There is also enough room there to park an RV overnight.

Saturday September 18th, Bayshore Live Oak Park, Bayshore Drive. Port Charlotte. 9 a.m. to noon, meet at the parking lot at Bayshore and Ganyard Street.

Sunday September 19th, Mead Garden: 1500 S. Denning Dr., Winter Park, FL 32789. 9 a.m. to noon. Meet at the bathrooms.

Saturday September 25th, Blanchard Park, 10501 Jay Blanchard Trail, Orlando, FL 32817. 9 a.m. to noon, meet by the tennis courts.

Sunday September 26th, Tide Views Preserve, 1 Begonia Street, Atlantic Beach Fl 32233 (near Jacksonville Fl.) 9 a.m. to noon. Meet in the only parking lot.

Saturday October 2nd, Eagle Park Lake, 1800 Keene Road, Largo, FL 33771. 9 a.m. to noon, meet at the pavilion near the dog park.

Sunday October 3rd, Boulware Springs Park, 3420 SE 15th St., Gainesville, FL 32641. Meet at the picnic tables next to the pump house.

Saturday October 9th, Putney Farm, South Carolina, classes at 9 a.m. and 1 p.m. each day. 1624 Taylor Road Honea Path, SC 29654.

Sunday October 10th, Putney Farm, South Carolina, classes at 9 a.m. and 1 p.m. each day. 1624 Taylor Road Honea Path, SC 29654.

For more information, to pre-pay or sign up go here.

Favolus is honeycombed underneath. Photo by Green Deane

There are between 2.2 and 3.4 million species of fungi. 2,000 or so are considered safe for human consumption. 350 species are collected and consumed as food, 25 species are widely grown commercially. 85% of the global edible mushroom production is in five genera: Lentinula, Pleurotus, Auricularia, Agaricus, and Flammulina. One of the irritating aspects of mushroom hunting is how many non-edible ones you find. Between the edible and non-edible ones are the semi-edible. Two genera come to mind, Lentinus and Favlous (and their renamed modern extensions like Neolentinus.) Favolus (whether called teniculus or braziliensis) are fairly easy to identify. Favolus is from the Dead Latin favus which means honeycomb. And indeed the underside of the mushroom is honecombed. They grow on wood — usually logs — in profusion and from a distance often makes the hunter think of oyster mushrooms. Tough even when cooked, they are 27% crude protein and 17% fiber. Some suggest boiling them first then frying. Expect them to be tough. They absorb flavors well probably because of the honeycomb gill structure. In the Amazon the Yanomami people eat and sell F. braziliensis and L. crinitus both of which grow here locally.)

There is a progression in the learning, or so I think. It’s usually starts with what we call weeds, small herbaceous green things around where we live. That takes a while. One problem is everyone wants to identify all the plants they see rather than actually looking for specific edibles. That makes the job harder. An easier way is to look for one edible or so per month when it is in season. About the time we are comfortable with low plants there are trees. They seem like difficult hunks and hard to tell apart. But trees nurtured humanity. The forest was not the dark dangerous place of fairy tales but ancient man’s grocery store, hardware store and pharmacy. Of all trees are the easiest to learn. You can study the same one 10 hours a day for a year and it won’t change much.

Non-native Crowfoot grass is easy to identify. Photo by Green Deane

After one gets a few trees down the next huge challenge is grasses. The difficulty of grasses is an almost completely new descriptive language and very small if not microscopic identification elements. Grasses are a pain in the … grasses. They can be extremely difficult. I am told by professors that grass taxonomists are so rare they can name their price and their employment is completely guaranteed. If you know a young person with an interest in biology it could be a good career. With grasses I am happy if I get the genus right, and a few of the species. The saving grace is, according to grass experts, there are no toxic native North American grasses. But many non-native grasses can be toxic… with cyanide. Grasses prepare you — psychologically — for mushrooms which overall I think are easier than grasses, certainly tastier. While perhaps not more complex they don’t live as long. Their quick growth makes them tough to learn in all their stages whereas an oak tree … is stoic.

Green Deane videos are now available on a USB.

My nine-DVD set of 135 videos has been phased out and replaced by a 150-video USB. The USB videos are the same videos I have on You Tube. Some people like to have their own copy. The USB videos have to be copied to your computer to play. If you want to order the USB go to the DVD/USB order button on the top right of this page or click here. That will take you to an order form. I’d like to thank all of you who ordered the DVD set over the years which required me to burn over 5,000 DVDs individually.

Green Deane Forum

Want to identify a plant? Perhaps you’re looking for a foraging reference? You might have a UFO, an Unidentified Flowering Object, you want identified. On the Green Deane Forum we — including Green Deane and others from around the world — chat about foraging all year. And it’s not just about warm-weather plants or just North American flora. Many nations share common weeds so there’s a lot to talk. There’s also more than weeds. The reference section has information for foraging around the world. There are also articles on food preservation, and forgotten skills from making bows to fermenting food.

The nose doesn’t always know.

The aroma of a wild food is the most flexible of all descriptions. This is for two reasons: Noses differ and plants differ. Taste is also quite flexible but aroma beats it out. When you read in a foraging guide, or even in my articles, that a plant smells like such-and-such know that the description is quite subjective. There are several local species that elicit different descriptions even when noses are whiffing the same sample. One low-growing fruit — the Gopher Apple — has been described as smelling like pink bubble gum, a new plastic shower curtain, or no aroma at all. The smelly spice Epazote ranges in opinions from citrusy to floor varnish to industrial cleaner. Even among non-edibles the olfactory estimations can vary such as with the toxic Laurel Cherry. Some think its cyanide smells like almonds, other think they smell maraschino cherries, some can’t smell the cyanide at all. Depending upon the population from 25 to 50% of folks can’t smell cyanide. In my classes we do sniff some cyanide-containing leaves. Is that dangerous? The short answer is no. You would have to inhale 135 ppm of cyanide some 25 minutes (at six breaths a minute) to have enough poison to affect you. The human nose can detect the aroma anywhere from 0.5 to 5 parts per million. From a survival point of view the nose would not been too good if it didn’t detect warning amounts. Interestingly our red blood cells prefer cyanide over oxygen. Once transported to our mitochondria the cynaide shuts down energy production. In guide books a reported aroma is just that, a guide. It is not always for certain by any means. There’s room for aromatic latitude.

This is weekly newsletter #474. If you want to subscribe to this free newsletter you can find the sign-up form in the menu at the top of the page.

To donate to the Green Deane Newsletter click here.

Green Deane…I am planning on attending your foraging class in Gainesville on October 3rd. Can you tell me the time to meet you there? It is not mentioned in the description above…Thanks, Owen Moore

9 a.m. at Boulware Springs pump house.