Among the identifying characteristics of this edible Bolete is red netting on the stem. Photo by Green Deane

We are in between mushroom seasons, so to speak. From about November to May most of the edible fungi we find grow on wood. From about June to November most of the edible fungi we find grow on the ground. May is an erratic transition month. For the summer season to start we need rain and warm ground (whereas in the fall dry and cooler stimulates some species.) Usually we get a couple of weeks of rain in May and that coaxes the mushrooms out of winter hibernation by June. Last year the lack of rain in May threw the season off badly.

This Florida Bolete defies edibility rules. Photo by Green Deane.

Thus I was not expecting to find an edible mushroom in last week’s foraging class in Port Charlotte last week (I did expect the bathrooms open but even the Port-O-Lets were locked!) Live Oak Park on Bayshore is not known for mushrooms. It’s on the cusp of being permanently too wet (thus in wet areas fungi often grow up on wood.) But we spied three Butyriboletus floridanus (BUET -ah- ree bow-LEE-tus flor-ree-DHAN-us) under a Live Oak. Though edible it brings up an edibility debate. The Bolete family in Florida is different than the Bolete Family in the rest of North America. Characteristics that can eliminate a Bolete from being edible up north don’t apply in Florida. So despite its coloring Butyriboletus floridanus is edible. I don’t think it has a common name. Maybe we can invent one (I did that for a different species and it has caught on.) This is definitely a Bolete (pores instead of gills) the cap is red and viscid, the cap and inner flesh stains blue when cut or bruised, the red stem is coarsely netted. The pores are red or orange and there are yellow drops on the pores when young. Spores olive brown. I eat the caps cooked. Lastly if we gt the several inches of rain they are predicting for this weekend maybe by next weekend the fungi will be flourishing.

Society Garlic is not mild-mannered. Photo by Green Deane.

You like garlic or you don’t. I worked with a piano player — Dennis Stiles — who loathed it and could detect it if you at it days earlier. Dennis, incidentally, lived to 105. My mother treated garlic … gingerly. When I was young if a recipe called for garlic my mother would rub one clove around the edge of what ever dish the food was going to go into. That was, for her, garlic seasoning which brings us to the backward history of Society Garlic which is blossoming nicely now. Settlers in South Africa considered clove garlic to be strong. Thus when going out on the town instead of eating regular garlic they had what they viewed as a milder native plant with a garlic aroma, Tulbaghia violacea. That has always struck me as odd in that Society Garlic is very intense. In my foraging classes when we pick it the aroma lingers for hours. Not native to North America and not wild but it is a common ornamental. To read more about Society Garlic go here.

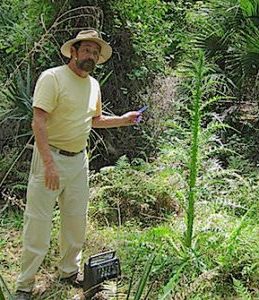

Gopher Apples look like tiny oaks. Photo by Green Deane

One might argue Gopher Apples get no respect. Barely noticeable they are blossoming now if you look closely. That usually requires bending over in that the species is often less than a foot high (though they can on occasion exceed that.) As you might expect their fruit is a common food of the Florida-protected species Gopher Tortoise (Gopherus polyphemus.) I must admit I have never seen a Gopher Tortoise in a patch of Gopher Apples. That may be because those reptiles prefer other species first: Broadleaf Grasses, mushrooms, saw palmetto berries, cactus pads, spurge, young pines, daisies, asters, blackberries, blueberries and Gopher Apples. They also eat carrion and manure. If you want to tell them apart the boys have long tails, girls short (probably so to not interfere with egg-laying.) You can read about Gopher Apples here.

Foraging classes are held rain, shine, hot or cold. Photo by Nermina Krenata

Rain and closed bathrooms makes classes a challenge this week. The Saturday class in Gainesville might get rained on. Dress for we and wind. Sunday’s class in Satasota should be dry AND the bathrooms are open.

Saturday, May 16th, Boulware Springs Park, 3420 SE 15th St., Gainesville, FL 32641. Meet at the picnic tables next to the pump house. 9 a.m. to noon. (This class date was originally at Spruce Creek in Port Orange but that had to be changed to Gainesville.)

Sunday, May 17th, Red Bug Slough Preserve, 5200 Beneva Road, Sarasota, FL, 34233. 9 a.m. to noon.

Saturday, May 23rd, Wickham Park: 2500 Parkway Drive, Melbourne, FL 32935-2335. Meet at the “dog park” inside the park. 9 a.m to noon.

Sunday, May 24th, George LeStrange Preserve, 4911 Ralls Road, Fort Pierce, FL, 34981. 9 a.m. to noon. (There is no official bathroom at this reserve.)

For more information, to sign up for a class, or to prepay go here.

Green Deane videos are now available on a USB.

Changing foraging videos: My nine-DVD set of 135 videos has been selling for seven years. They are the same videos I have on You Tube. Some people like to have a separate copy. The DVD format, however, is becoming outdated. Those 135 videos plus 15 more are now available on a 16-gig USB drive. While the videos can be run from the DVDs the videos on the USB have to be copied to your computer to play. They are MP4 files. The150-video USB is $99 and the 135-video DVD set is now $99. The DVDs will be sold until they run out then will be exclusively replaced by the USB. This is a change I’ve been trying to make for several years (with thanks to Mike Smith.) So if you have been wanting the 135-video DVD set order it now as the price is reduced and the supply limited. Or you can order the USB. My headache is getting my WordPress Order page changed to reflect these changes. We’ve been working on it for over two weeks. However, if you want to order now either the USB or the DVD set make a $99 “donation” using the link at the bottom of this page or here. That order form provides me with your address, the amount — $99 — tells me it is not a donation and in the note say if you want the DVD set or the USB.

Nickerbean pods protect the gray seeds.

Botany Builder #28: Echinate, covered with spines or prickles. It is from the Dead Latin echinatus, covered with prickles. Sea urchins are in the class of Echinoidea. “Urchin” by the way is an old word for porcupines as is hedgehogs. Mischievous boys are some times called urchins. Locally one medicinal plant is echinate, and that is the Nickerbean. Not a vine and not a tree, it is a “climbing shrub.” The Smilax is also not called a vine but a “climbing shrub.” The Nickerbean is not edible, but does, according to herbalists, have many medicinal applications as a quinine substitute To read more about the Nickerbean go here.

Passiflora incarnata and unripe fruit. Photo by Green Deane

It’s June and Maypops are popping out all over. They are easy to find: Look for a vine that has three-lobed leaves and smooth, green fruit shaped like a large egg to a tennis ball. The fruit ripens to yellow near the base of the vine first. The plant, which smells like an old gym shoe, will put on new fruit until cold weather. Green fruit can be fried like green tomatoes. Sometimes the green ones have seeds mature enough to be tart. Sweet and sour seeds can be scooped out of the yellow fruit and eaten along with their white jelly-like coating. Locally our most common passion fruit is Passiflora incarnata, right. You will read on the Internet that it contains cyanide. It does not though many passion fruits do if not all but P. incarnata. It was specifically tested and definitely does not have cyanide in it’s leaves. The varying amounts of cyanide in other species of passion fruit is one reason why animals don’t eat them and one reason why you should not eat any ornamental passion fruit you may have. Instead of cyanide P. incarnata has GABA, gamma-Aminobutyric acid, which calms you down. It might be a possible anti-dote for Water Hemlock poisoning in that Water Hemlock breaks down the body’s reserve of GABA.

The Cherry Laurel is deadly. Do not eat it. Photo by Green Deane

Mentioning cyanide many plants have it, including several edible species, Chaya for example. Mechanical breaking down of plant cells or cooking often gets rid of the cyanide which many times is bound together either with sugar or hydrogen. Sometimes the plant has to be fermented so the bacteria can eat the glucose thus freeing the cyanide to be rinsed away. Clearly one wants the cyanide to be released outside of the body not during digestion. The toxic non-edible Cherry Laurel is a common poisonous plant with the cyanide bond. If you crush a leaf you can smell either almonds or “maraschino” cherries. That’s cyanide. However, there is one interesting fact you should keep in mind: Depending where you are only 25 to 40% of the population can smell cyanide. It’s a gene-linked thing. If you can crush several Cherry Laurel leafs and not smell almonds or “maraschino” cherries you might be one of those who cannot use their nose to detect cyanide. You can, however, look at the backside of the leaf near the stem and find two faded dots. Those can help you identify it. The fruit is also deadly. Just leave it alone.

The white, fluffy home of dye bugs. Photo by Green Deane

You eat a lot of bugs, you just don’t know it. For example: One cactus species is called Opuntia cochenillifera. Cochenillifera in Dead Latin means “cochineal bearing” but is from the Greek word for red, “kokinos.” That’s because the cochineal insect lives off the cochenillifera cactus and others. You might find that almost interesting except you’ve eaten that exact insect or more specifically a product produced from their crushed, little dehydrated bodies: Cochineal dye, also called “Tuna Blood.” Actually, only the female cochineal bug provides the red dye and it takes some 75,000 to make one pound, 155,000 to the kilogram. Sometimes in the wild you will see a Nopales or an Opuntia mottled with white or gray, or even covered with white or gray cotton-like covering (see photo to right.) That’s a cochineal condo. The hard part is each of the scale-like insects has to be harvested by hand, when they are around 90-days old.

Several food and cloth dyes can be made form the little Cochineal bug.

Before artificial dyes were invented, cochineal dye was the main red dye from fabrics to food. In the 1400s, eleven cities conquered by Montezuma each paid a yearly tribute of 2,000 decorated cotton blankets and 40 bags of cochineal dye. During colonial days Mexico had a monopoly on cochineal dye and it was that country’s second largest export after silver. Cochineal went out of favor and flavor when chemical dyes came in but the organic movement and rejection of artificial dyes has brought it back. Cochineal trumps chemicals unless you’re a vegetarian who have protested its recent incursion into “natural” foods. Others oppose its use because the only religiously approved insect to consume is the locus. If you use a cosmetic — red lip stick for example — or have eaten a product with any of the following ingredients, you have used or bitten the bug as they are all different names for the same insect coloring: Cochineal Extract, Carmine, Crimson Lake (or Lac) Natural Red 4, C.I. 75470, E120, or even “Natural Coloring” when the product is any shade of red, scarlet, purple or orange. Cochineal is also one of the few water-soluble dyes that resist fading. It is used also in slide staining (you remember those pink slide from biology 101 don’t you?) There is a bug in your past, and probably your future.

Green Deane Forum

Want to identify a plant? Perhaps you’re looking for a foraging reference? You might have a UFO, an Unidentified Flowering Object, you want identified. On the Green Deane Forum we — including Green Deane and others from around the world — chat about foraging all year. And it’s not just about warm-weather plants or just North American flora. Many nations share common weeds so there’s a lot to talk. There’s also more than weeds. The reference section has information for foraging around the world. There are also articles on food preservation, and forgotten skills from making bows to fermenting food.

This is weekly newsletter 405, If you want to subscribe to this free newsletter you can find the sign-up form in the menu at the top of the page.

To donate to the Green Deane Newsletter click here.

How about Florida bolete as a common name for Butyriboletus floridanus? I’m using it as the common name for the species in an article I’m writing for a client.