Persimmons can persists after the leaves drop making them easy to spot.

Persimmons: Pure Pucker Power

About the only bad thing you can say about a persimmon is that it has pucker power, if you pick it at the wrong time. If the fruit’s skin isn’t wrinkly it will be inedible.

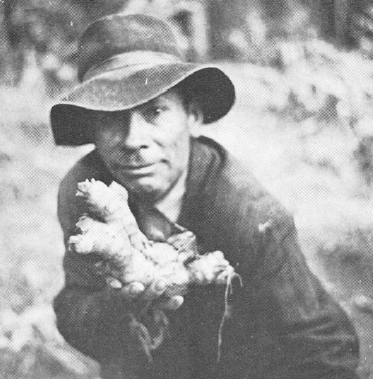

You have competition for ripe persimmons.

What most people don’t know is that the persimmon is the North American ebony, Diospyros virginiana (dye-OSS-pih-ross ver-jin-nee-AY-nuh.) There are few trees more versatile than the persimmon. The fruit, actually the largest native berry in North America, can be eaten out of hand or cooked in various ways. Its seeds can be roasted and ground for a coffee extender. The leaves are loaded with Vitamin C and the hard, closed-grain wood can be worked (often to be made into “natural” wedding bands. )

Persimmons do not like to grow in the forest or field.

Persimmons like to grow along the edges of things; fields, roads, rivers, rail roads, fences, trails. They can be anything from a spindly shrub to over 80-feet tall. I can well remember the first time I found a green persimmon fruit on the ground locally. I was hiking in the Wekiva State Park in Florida along Rock Springs Run. What was memorable about the event was I couldn’t find the tree. I turned 360 degrees and still couldn’t see a persimmon tree until I looked up, way, way up. Competing with other trees river side they were incredibly tall, and not nine inches through. They were spindly 70-foot tall trees! Quite atypical.

Most of the persimmons trees you will see, especially in Florida, are only eight to ten feet tall, occasionally 15 to 20 feet. Persimmons are found in the eastern half of the United States excluding northern border states. They’re also found in Utah, California and range into Mexico. Oddly, they are not naturally found along the Appalachian Mountains or the Allegheny Plateau. Perhaps altitude is an issue.

The Persimmon’s native range.

The Persimmon is usually the last tree to leaf out in the spring and the first to lose it leaves in the fall, a strategy to thwart predatory insects. The champion persimmon tree in the US, as of 2009, is in Yell, Arkansas. It is 94 feet high, 12.5 feet around and as a crown spread of 78 feet. It’s been around since the first English settlers came to North America. One of them, Captain John Smith, wrote about the persimmon in 1608. He said it tasted like an apricot and by 1629 it was introduced into England. In fact that was a main part of Smith’s reason to come to the Americas, find new plants.

Persimmons get smutty but the black smut does not bother it nor us. Photo by Hillpond.org

While many authors say the ripe persimmon tastes like dates they taste like persimmons to me. I have no idea where they get a “date” taste unless they are just copying each other. Interestingly persimmons can be interchanged in any recipe with bananas, measure for measure, weight for weight. Yellow persimmons will ripen off the tree but the best ones are the wrinkly ones you have to fight the ants for. There is an old saying that persimmons don’t ripen until after a frost but that’s not true according to researchers nor here in Florida where any frosts show up a couple of months after persimmons fruit. Shaking a persimmon tree is the standard way of collecting the fruit. Process them by rubbing them through a colander. The pulp can be used to make jelly, syrup, beer, wine, liquor, bread, pancakes, pudding, molasses, fruit leather, dried fruit and ink. The pulp can also be frozen and eaten like ice cream. A peanut-like cooking oil can be squeeze from the seeds. Each persimmon can have one to eight seeds. Happiness is finding a persimmon with one seed, when there are eight there isn’t much to eat. The seeds, however, were used as buttons by the Confederate Army during the American civil war.

The fruit, especially the skin, can be made into fruit leather. Photo by KerbieCravings.

Another use for a persimmon tree is reportedly as a remedy for the itch of poison ivy. Remove a few twigs from a persimmon tree, cover with water, and boil for 20 minutes. Strain and cool the liquid. Several applications are said to dry the rash. By the way, persimmon tea is not universally praised. I have a friend who describes the taste of tea from green leaves as “dirty dishwater.” Tea from dried leaves is better. In fact, the longer the dried leaves are stored the better the tea tastes. Dry the leaves in a slow over for two hours. To make the seeds into a coffee substitute or extender clean them and roast them in the same slow oven. You can also throw the tough fruit skins into a blender, put the slurry on a cookie sheet and dry them along with the seeds and leaves in the same oven. Personally I eat the fruit skin and all but not the seeds

As an ebony, Persimmon wood has many uses.

What Diospyros means is subject to a lot of mistranslation from Greek. The complicating factor is the distortion from Greek to Latin and the different alphabets and pronunciations. (There are five ways to represent the “ee” sound in Greek.) Then there’s the translation into English and its use by those who don’t speak Greek or know Latin. Such is the headache with Diospyros. Briefly it can mean “what God has sown” “God’s Grain” or “God’s fire.” Making it worse, the most common translation “food of the Gods ” does not land well on Greek ears. Ambrosia means “food of the gods. Diospyros does not.

Theostratus coined the name Diospyros

In 300 BC or there abouts, Theophrastus called a local tree, the European hackberry, Diospyros. The fruits were astringent which ripened to sweetness and that is supposedly why Linnaeus called the persimmon tree Diospyros when he was naming plants. With that said lets tackle Diospyros. The disagreement is whether the two Greek words are “dio/spyros” or “thios/piros.” It comes down to Greek spelling. The most common translation is the more unlikely. As mentioned, Diospyros is often translated as “fruit of the gods” or “food of the gods.” That would be very bad Greek. Some translate Diospyros as “the fruit of Zeus” which is just plain silly. There’s also “heavenly plant” “God’s fire” Divine pear” and “Jove’s pear.” Jove’s Pear? That’s expired poetic license. Jove was the Roman equivalent of Zeus, or the Roman name for the top god. Where the pear came from I have no idea though in Texas the persimmon is sometimes called Jove’s Fruit.

Roasted Persimmon seeds can be used to extend coffee. Photo by Really Raw Food.

A third possibility is Diospyros meaning “God’s Fire” in reference to the astringent unripe berries of the European hackberry but that would require changing a plural to a singular which is not likely in this case in Greek. Carl Linnaeus, the fellow who started naming plants, had the right idea of calling the persimmon after the ancient hackberry because of the way it ripens. He was not good at Greek yet his “food of the gods” has stuck. “God’s Wheat” is the closer translation for ancient Greek, which would mean the Diospyros in the modern vernacular means the “best food” or as Alton Brown says “good eats.”

Horses should not be pastured with Persimmons or they can get bezoars, as can some people.

Virginiana is of Virginia but in botanical terms it always means North America. Persimmon is the Anglicized version of an Algonquin name that means “dry seed” or “dry fruit” referring to the high level of tannins in the unripe fruit. That tannin is a good substitute for oak tannin. Persimmons do, however, come with two warnings. The first one is if you do not digest food well or have had gastric bypass surgery excessive consumption of persimmons can create intestinal blockage called a bezoar. It happens more in farm animals than man but people who consume huge amounts of persimmons or who have gastric issues are at risk.

Nothing resembles a ripe wild persimmon tree.

As for the second warming. While the seeds can be roasted then ground into a black powder to extend coffee there may be reasons not to use it exclusively as a coffee substitute. See the “letter to Green Deane” below. The writer mistakenly made “coffee” out of the seeds rather than using them as a coffee extender, like chicory. It is included here in its entirety should it be important some day.

There is hardly a woodland creature that doesn’t like the persimmon. Its waxy, fragrant flowers help produce honey. The persimmon is also sometimes called “possom wood” because opossums know a good food when they find it. It even has entered the folky and now politically incorrect literature of Uncle Remus:

Even Green Deane breaks his no-flour rule for some hot Persimmon bread.

“B’rer Bear rushed into the patch and shook the persimmon tree. B’rer Possum dropped out from the ripe persimmons, landed on the ground and started running for the fence like a race horse. B’rer Bear chased him and gained with every jump. When B’rer Possum made it to the fence B’rer Bear grabbed him by the tail. B’rer Possum went between the rails on the fence and gave a powerful pull to get this out of B’rer Bear’s teeth. B’rer Bear was holding so tight and B’rer Possum pulled so hard that all the hair came off in B’rer Bear’s mouth, and if B’rer Rabbit hadn’t come along with a gourd of water B’rer Bear would have choked. From that day to this,” said Uncle Remus, knocking the ashes carefully out of his pipe, “B’rer Possum ain’t had no hair on his tail, nor any of his children.”

Persimmon Bread

3½ cups sifted flour

1½ teaspoons salt

2 teaspoon baking soda

1 teaspoon ground nutmeg

2 to 2½ cups sugar

1 cup melted unsalted butter and cooled to room temperature

4 large eggs, at room temperature, lightly beaten

2/3 cup cognac, bourbon or whiskey

2 cups persimmon puree

2 cups walnuts or pecans, toasted and chopped

2 cups raisins, or diced dried fruits (such as apricots, cranberries, or dates)

Optional: Orange zest or orange extract

1. Butter 2 loaf pans. Line the bottoms with a piece of parchment paper or dust with flour and tap out any excess.

2. Preheat oven to 350 degrees.

3. Sift the first 5 dry ingredients in a large mixing bowl.

4. Make a well in the center then stir in the butter, eggs, liquor, persimmon puree then the nuts and raisins.

5. Bake 1 hour or until toothpick inserted into the center comes out clean.

Persimmon Pudding

2 cups pureed persimmon pulp

2 eggs

1 3/4 cups condensed milk (unsweetened)

2 cups sugar

1/4 cup melted butter

2 cups flour

1/2 cup chopped walnuts

Stir condensed milk, sugar, butter, flour, and persimmon puree well and pour into glass baking dish. Sprinkle top with chopped walnuts. Bake for 35 to 45 minutes at 375F. Serve warm or cooled to room temperature. Delicious topped with a crème Anglaise or rum.

Green Deane’s “Itemized” Plant Profile

IDENTIFICATION: Tree, shrub size to 80 feet, usually 15 to 20. Leaves are oval, pointed, 3- to 6-inch long, lustrous dark green, sometimes covered with a harmless dark soot that can be washed off. Two handy identifying characteristics of the persimmon is young twigs are fuzzy and on new growth the branch will have leaves of different size. Bark on older trees is broken up into square blocks. D. virginana has leaf tips that are pointed, on D. texana the tip is flat, rounded or notched,

TIME OF YEAR: Fruit ripens in September/October. Fruit is not ripe until the skin is wrinkled.

ENVIRONMENT: Grows along edged of fields, roads, rivers and the like. Will grow in dry ground and partial shade but prefers moist soil and full sun. Slow growing, hardy to Zone 4

METHOD OF PREPARATION: Numerous: The pulp can be used to make jelly, syrup, beer, wine, liquor, bread, pancakes, pudding, molasses, fruit leather and dried.

HERB BLURB

The Native Americans had some herbal uses for the tree. The Alabama boiled the roots for a tea used in “bowel flux.” The Catawba used a bark infusion to treat thrush in babies. The Cherokee used it for bowel problems, sore throats, heartburn, liver problems, piles, thrush, toothaches and venereal disease. The Rappahannock used an infusion for thrush and sore throats. The tannic acid in the green fruit was used to treat diarrhea, dysentery, and uterine bleeding.

I received the following letter in 2010 in response to my article on persimmons. The writer says he made two pots of persimmon “coffee” rather than using the ground seeds just as a coffee extender. The first pot — four cups — was made from seeds fresh from ripe fruit off the tree, then roasted. No ill effects reported. The second pot was made from seeds picked up off the ground and/or from rotting fruit (enzyme action?) Then instead of directly into the oven the second batch of seeds were boiled first (taking something away? Changing something?) and then roasted. Two other possibilities are the first pot did not reach some critical chemical level and or he didn’t have an allergic reaction until a certain point with the second pot. And of course something else might be acting as well. I do not know the truthfulness of the account below but it seems reasonable to include it. More so, if it is accurate it is something foragers and researchers should know.

“I just wanted to shoot you a quick note about my experience with Persimmon seeds last fall, sorry it took so long for me to write. I have several of the trees in my yard and near my home, and I always enjoy the fruit in the late fall after frost. But I had never heard of making coffee out of the seeds before. Being the adventurous sort I gave it a try, and my first pot of roasted and ground up seeds taken from the fresh fruit right off of the tree was wonderful, thank you.

“Later I began collecting the seeds off of the ground around the trees where the fruit had fallen off and rotted, carefully avoiding the piles of possum poo of course. When I had about a quart of seeds I put them in a small saucepan and boiled them for about 5-10 minutes to kill any bacteria and clean the residue off of the seeds, then I slow roasted them on about 250 until I could hear them steadily crackling and popping.

“After the seeds had cooled I anxiously ground up a handful for a full eight cup pot of coffee. My first pot from the earlier experiment was only about four cups. I brought my fresh, large mug of coffee (About 3.5 cups) to the computer and I enjoyed it immensely while watching videos. But almost as soon as I began the second mug full I began to feel a little funny. In a few minutes I became dizzy and stopped drinking. A few more minutes passed and I became very ill and evacuated my stomach of any remaining persimmon coffee lol.

“I have a heart condition so I made sure that I was not in cardiac distress, and when everything seemed OK i stumbled off to bed. The next day, after a very sweaty night, I still felt a little peculiar, which is not unusual for me. But I was no longer dizzy or nauseous.

“Now for the really interesting part. I have Cardio Myopathy and severe heart disrhythmias, so I can usually feel my heart skipping and pounding. But for about three months after this incident I was like a normal person, heart rhythm wise that is lol. I have actually been able to feel my heart beat since I was a young boy, and I have only rarely had a steady rhythm for short periods. So not being able to feel my heart beat or detect rhythm problems was phenomenal for me.

“My heart is back to its normal skipping and pounding now, and I have been trying to decide if it was worth the risk to try lowering the dose of persimmon coffee down to a sip or two and see if I get positive results. I am not writing for advice because I know that it would be too much of a liability for you to give me the go ahead on something like that, but I did want someone to know what had happened with my adventure in drinking persimmon seed coffee.”