Some Honeysuckles are edible, some are toxic

Lonicera japonica: Sweet Treat

The honeysuckle family is iffy for foragers. It has edible members and toxic members, edible parts, toxic parts, and they mix and match. Some are tasty, some can stop your heart. So you really have to make sure of which one you have and which part is usable and how.

On the top of the common list is the Japanese Honeysuckle. It is the honeysuckle kids grew up with, picking the flowers for a taste of sweetness. Young leaves are edible boiled. In my native state of Maine there is the L. villosa, the Waterberry, some times called the Mountain Fly Honeysuckle, with edible berries. It is also sometimes mistakenly called L. caerulea (which is European.) Let me see if I can clear that up: If it refers to L. caerulea as edible it is usually L. villosa which is actually being identified (Waterberry.) If it is L. caerulea and toxic it is usually the L. caerulea in Europe that is being referred to. How the L. villosa in North America got referred to as L. caerulea is anyone’s guess. Anyway, the Waterberry berries are quite edible.

Among the edible are: L. affinis, flowers and fruit; L. angustifolia, fruit; L. caprifolium, fruit, flowers to flavor tea; L. chrysantha, fruit; L. ciliosa, fruit, nectar; L. hispidula, fruit; L. involucrata, fruit; L. kamtchatica, fruit; L. Japonica, boiled leaves, nectar; L. periclymenum, nectar; L. utahensis, fruit; L. villosa, fruit; L. villosa solonis, fruit;

Among those that might be edible or come with a warning of try carefully are: L. canadensis, fruit; L. Henryi, flowers, leaves stems; L. venulosa, fruit.

There are about 180 species of honeysuckle, most native to the northern hemisphere. The greatest number of species is in China with over 100. North America and Europe have only about 20 native species each, and the ones in Europe are usually toxic. Taste is not a measure of toxicity. Some Lonicera have delicious berries that are quite toxic and some have unpalatable berries that are not toxic at all. This is one plant on which taste is not a measure of edibility. Properly identify the species.

Species in the genus are quite consistent. The leaves are opposite, simple, oval. Most loose their leaves in the fall but some are evergreen. Many have sweetly-scented, bell-shaped flowers with a sweet, edible nectar. The fruit can be red, blue or black berry, usually containing several seeds. In most species the berries are mildly poisonous, but a few have edible berries.

While the flowers are a popular nectar source for bees and butterflies L. japonica is considered an invasive weed throughout the warmer parts of the world, from Fiji to New Zealand to Hawaii. It was introduced to the United States about 200 years ago and because it has no natural enemies here has been spreading ever since. In my own yard it has proven to be very invasive, not only up but out. I’ve had a several year battle with it trying to cover a pear tree and a grape arbor.

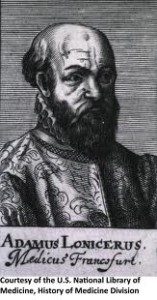

Lonicera japonica is pronounced lah-NISS-ser-ruh juh-PAWN-nick-kuh. The genus was named after Adam Lonitzer (1528-1586) a German physician and botanist. Japonica means of Japan

Green Deane’s “Itemized” Plant Profile

IDENTIFICATION: Lonicera japonica: A vine to 80 feet, twining, trailing, thin, sometimes rooting at nodes, reddish to brownish or purplish, younger parts hairy, often with thin woody bark on the lower stems. Leaves – opposite, with stems or without, leaves variously hairy above and below but typically densely hairy, no teeth, ovate-oblong, pointed tip, rounded to heart-shaped at base. Flowers white, drying to yellow, a tube, upper lip 4-lobed, bottom lip single-lobed, Stamens 4, filaments hairless, white, style white, stigma green. Fruits black, fleshy globes, not edible.

TIME OF YEAR: Leaves when in season, flowers May to July in northern climes, nearly year round where it is warm

ENVIRONMENT: Landscaping, naturalized in open woods, thickets, roadsides, railroads

METHOD OF PREPARATION: Nectar sucked off the ends of the flowers, young leaves boiled. In China leaves, buds and flowers are made into a tea but the tea may be toxic. Proceed carefully.